Conceptual Frameworks

The principles on which we base our recommendations, tools and tips for inclusive teaching. On this page, you will find the conceptual frameworks that guided the development of this website. They will help you understand the foundations of inclusive pedagogies and strategies.

Culturally responsive teaching (CRT)

Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT) is defined as an approach that includes all students in the learning environment.

It takes into consideration the context of each individual and links it to what is taking place in the course. “Context” refers to knowledge, experiences, and perspectives, all of which are influenced by culture, the socialization context, and so on. It means we must get to know our students in order to support them fully in this inclusive learning process.1

Culture determines how we learn. The way we receive, perceive, and communicate information is influenced by our beliefs, just as the way we think, the way we perceive the group to which we belong, and the way we work, organize our ideas and thoughts, the way we motivate ourselves, and the way we interact, are influenced by culture.

Furthermore, Culturally Responsive Teaching sees learning as a process that is not related solely to the cognitive or intellectual sphere. Learning also impacts the emotional, social, and physical spheres (learning by doing) and the quest for meaning (which some people call spirituality; authenticity, engagement, connections to life in general, and so on).

Taking culture into account in the way we teach (presentation of the subject, assessments, types of activities and assignments, atmosphere in the classroom) promotes learning and academic success. Culture acts as a filter. Thus, we must remember that our attitudes and behaviours significantly affect how such factors as the class, teacher, and atmosphere are perceived by students. In turn, this influences the sense of belonging to the class, drop-out rates, and academic success.

To support inclusive teaching, CRT proposes four core principles to consider:2

- Our ability to concern ourselves with the well-being and academic success of all students, regardless of the group to which they belong or with which they associate.

- The way in which we communicate (message type, style, concern for equity taken into account in individual contexts, etc.).

- The framework with which we teach (content, course/curriculum structure, educational design, etc.).

- The way in which we teach (attitudes, approaches, and behaviours).3

Note: CRT also means Critical Race Theory. In this page, CRT refers to Culturally Responsive Teaching.

Applying UDL and CRT is a powerful shift in making our classrooms a space for all learners – individual students have more of an opportunity to see themselves reflected in the work they are being asked to do, which in turn creates a more inclusive community and helps model the professional world our students will soon enter.

(Bass & Lawrence-Riddell, 2020, para. 5)

These are all aspects we can influence. How?

Here is an overview of strategies that are regularly cited in that regard.4 For a more detailed list, see Page 4 - Strategies and Tools on this website:

- Give students the opportunity to talk about their realities (emotions, beliefs, values, perspectives) so they belong to the group and can contribute to their full potential (self-worth, self-esteem, etc.).

- Establish links between course content and “real life” (authenticity and relevance) by holding discussions as well as practical problem-solving and reflection activities. This strategy will allow students to process the material in the light of their own contexts and filters, which increases knowledge assimilation and strengthens inclusivity and teaching quality.

- Use a variety of examples to ensure greater representation, to maximize learning and concept comprehension, as well as to bridge gaps between old and new knowledge, between the known and the unknown, and between the abstract and reality.

- Use a variety of teaching and assessment methods to reach as many students as possible and to meet a wide range of needs and ways of learning. To that end, give students choices and support at the right time (scaffolding), and communicate instructions and expectations explicitly.

CRT requires that you reflect on your teaching practices on a regular basis. It is an effective way to spot your unconscious biases,5 to adapt your teaching methods and your interactions with students, and to adopt a more conscious approach.6 For more information, see Page 2 – Context and Considerations.

Critical pedagogy

This movement is often associated with Paolo Freire and his Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970). The thrust of this movement is to raise the awareness of the people through education regarding the power, authority, and normalization aspects at play in society that keep them in an oppressed state. By developing critical thinking skills in their students, teachers encourage them to act in a cyclical manner (theory, application, assessment, and reflection) to bring about change.

It should be noted that in this context, the learning environment is not neutral or free of political considerations. It is the role of the teacher to humbly pull back the curtain on these issues, to raise the participants’ awareness, and to guide them in the cycle that leads to action, by aiming for access to resources and equity with respect to the dominant group10.

Critical theory

Critical theory,11 which we owe to Max Horkheimer’s 1937 essay titled Kritische Theorie in German, holds that knowledge is a social construct influenced by the people who develop it. It reflects the values, culture and hierarchy of the social group or groups, and the interests of the people involved. Critical theory challenges presented and accepted knowledge and broadens its scope by questioning it and adding new information. Sensoy and DiAngelo (2017) suggest that, in education, this theory challenges the neutrality of knowledge, encourages student self-reflection in order to develop an awareness of one’s subjectivity; and promotes the development of skills that are needed to analyze dominant ideologies in a particular discipline.

The goal of education is to expand one’s knowledge base and critical thinking skills, rather than protect our pre-existing opinions. (…) there will be no personal or intellectual growth for us if we are not willing to think critically about them.

(Sensoy and DiAngelo, 2017, p. 33)

SJE is also based on principles deriving from social psychology and Western pedagogies that promote inclusion, e.g. learner-centred teaching, experiential approaches, critical thinking, social constructivism, openness to diverse contexts and perspectives, and numerous other approaches.

Examples and derivatives: decolonization, critical race theory and critical gender theory

Decolonization, critical race theory and critical gender theory are briefly described below to illustrate the impact and influence of SJE. These descriptions are not only informative but also provide an overview of the inclusive teaching process. You will see similarities between methods for decolonizing, fighting racism, and promoting gender equity (and other equities). Although their foundations may vary, social justice is the common thread that runs through them. Page 5 – Resources of this website contains resources to further explore these concepts, understand their nuances, and appreciate their effects.

Examples

Canada’s education system, like Canadian society in general, is largely influenced and guided by dominant Western ideologies and norms. The Indigenous communities of Turtle Island (also known as North America) do not recognize themselves in what is being taught or in the ways learning occurs in Canadian schools, colleges, and universities. This lack of recognition is part of what was taken from them. It is a part of colonization.

Dominant Western education and related ideologies continue to be a major system and mechanism for the exercise of dominant power and privilege (…) which ideologically prepare students for appropriate and effective citizenship. (…) [I] continues to be a central site of privilege, power, domination, and control for the expansion of nationalistic culture and ideals.

(Styres, 2017, p. 97)

Knowing this, how should courses, programs and teaching methods be redesigned to address the power differential, learning barriers, and the need to offer a more inclusive learning environment?

First, as educators, we should begin by learning about Indigenous perspectives (history, cultures, philosophies, pedagogies, etc.). We should also be looking both inward and outward when we create spaces for Indigenous students to welcome them and provide a relevant and contextualized learning experience.

Decolonizing requires developing a critical consciousness about the realities of oppression and social inequities for minoritized people.

(Tuhiwai Smith et al., 2019, p. 32)

Second, as educators, we should reflect on the way we teach, on what our teaching practices are based on, and to whom we really are teaching (see Page 2-Context and Considerations to explore these questions in greater depth). To decolonize, we need to revisit the learning environment, meaning what happens in the classroom (virtual or physical) and outside of it (e.g., group work after class). The decolonization of courses and programs most importantly requires that we learn how to share both the teaching and learning space and the power dynamic with students in the classroom.

In this way, the students’ voices will be heard; they will be able to choose how learning takes place; they will acquire the knowledge and develop the skills that are mindful of context and culture; and the Indigenous students will not only recognize themselves in the learning community but also be part of it.

As educators, how can we move beyond the status quo to improve the learning environment for Indigenous students to allow them to thrive?

The four frameworks presented in this page are designed to promote decolonization as part of a holistic inclusive teaching process. As we further explore Western and Indigenous pedagogies related to inclusive teaching, we will also discover various forms of decolonization.

Resources for learning more about decolonization

-

Styres, S. (2017). Pathways for remembering and recognizing Indigenous thought in education: Philosophies of Iehti’nihsténha Ohwentsia’kékha (Land). University of Toronto Press.

-

Elders and Traditional Knowledge Keepers: uOttawa Guide to Indigenous Protocols

-

Donald, D. T. (2009). Forts, Curriculum, and Indigenous Métissage: Imagining Decolonization of Aboriginal-Canadian Relations in Educational Context. First Nations Perspectives, 2(1), 1–24.

-

Gaudry, A. & Lorenz, D. (2018). Indigenization as inclusion, reconciliation, and decolonization: navigating the different visions for indigenizing the Canadian Academy. AlterNative: An International Journal of Native People, 14(3), 218–227.

-

Adams, M. and Bell, L. A. (eds.). (2016). Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice (3rd ed.). Routledge.

This movement, which emerged in the 2000s, is often associated with researchers Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic. Critical race theory seeks to describe and explain concepts of race and racism in the particular context of a society dominated by white normalization. In this context, race is a social construct whose purpose is to subjugate minority groups, i.e., Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC), to the dominant group (whites).

Critical race theory challenges the status quo, particularly in terms of ideologies, history, legislation, and culture. Through the questions it raises and ensuing analyses, patterns of inequality emerge, along with the disadvantages suffered by subjugated groups. Critical race theory also prompts an evolution in thinking as well as actions aimed at reducing systemic racism.

In terms of antiracism and decolonization, we, as teachers, must remain informed about BIPOC history and culture, learn about institutional inequities, reflect on our teaching practices, be open to different reflection frameworks and strategies (see the resources on this website), and become allies in the classroom. In so doing, we will break down barriers to learning, increase student retention, and promote student academic success.

This movement is associated with the work of feminism, sexuality studies, Queer theory and gender/masculinity studies. These theories explore how gender is commonly represented by dominant groups and sexual orientations, specifically cis-men and those who identify as heterosexual. More women than ever before are entering higher education, signalling an improvement in equity, which in turn underscores the importance of recognizing gender as non-binary, fluid, and socially constructed. When we apply critical gender theory, we see the classroom is a site of gender relations where “student” identity typically implies being a young, middle-class male raised in a consumer culture. These socially constructed dynamics serve to limit the power of those who identify physically or psychologically in other ways, such as female, non-binary, and/or as LGBTQIA+. Our educational spaces and systems are influenced by the impact of social relationships between male and female identities.

[W]e have a duty to foster an environment that equips students to translate all that they are learning into the world – a world of power relations, institutional inertia, gendered understanding, and deep but not immovable inequalities

(Silver, 2018)

Some stereotypes of feminism assume an anti-male, pro-lesbian or women-only allyship, which is false. In advocating for the rights of women across various waves of feminism, critical gender theory raises the visibility and voices of underrepresented genders and sexual orientations, along with many other intersections of identity in society.

Social biases tend to associate strength with masculinity, or relationships with romantic, monogamous partnerships. By exploring these biases through the lens of a more inclusive approach to education, we help break down these barriers. Our course design choices can allow us to share the classroom space with the many voices and identities in the room. Through the way we conduct ourselves online and in class, ideally by implementing inclusive teaching practices (e.g., using preferred pronouns), we can support the range of non-binary genders and model acceptance in the class space. Another inclusive choice would be to vary examples, such as presenting a case study involving a woman and mother of colour, for example.

Universal design for learning (UDL)

Supported by educational neuroscience research, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a model that was originally developed to support persons with disabilities. Its principles and strategies are now recognized as being beneficial for students from all walks of life. UDL takes into consideration individual contexts, abilities, and learning needs in our teaching practices. It requires a paradigm shift from teacher-centric to student-centric in the design and delivery of courses and programs.15 Expressions such as “the myth of the average student” and “diversity is the norm, not the exception” were coined by UDL pioneers.16

UDL encourages us to stop thinking about people as needing to make progress or be fixed because they come from minority groups or because they have physical, sensory, cognitive or emotional disabilities, for example. Instead, UDL prompts us to consider these people as coming into the learning environment with their own context, goals, and abilities, and as wanting to be recognized for who they are and for what they can contribute to enrich the learning experience of all students.17

The UDL framework (…) recognizes and celebrates our differences and the need for flexible learning environments.

(Friztgerald, 2020, p. 13)

UDL is about reducing barriers to learning and fostering student academic success and holistic development. It also seeks to level the playing field by offering equitable chances of academic success, not unfair advantages. UDL is not about lowering expectations and academic standards. It is about providing flexibility and choices in the ways students can demonstrate their knowledge and skills, considering their strengths, interests, context, as well as previous knowledge and experiences.18

Options are essential to learning, because no single way of presenting information, no single way of responding to information, and no single way of engaging students will work across the diversity of students that populate our classrooms. Alternatives reduce barriers to learning (…) for everyone.

(Tobin & Behling, 2018, p. 24)

UDL has a set of principles19 leading to strategies for teaching and supporting learning.

CAST is known for having developed UDL guidelines, which have been described and adapted by various authors and researchers. They include the three main guidelines below:

Principle 1:

The "why" of learning

Multiple means of engagement through affective networks in the brain.

These strategies improve the perseverance and motivation of learners.

- Optimize choices, autonomy, relevance, authenticity, safety and focus (versus distractions).

- Foster goal setting, coping skills, confidence, self-assessment, self-reflection and collaboration.

- Provide challenges and feedback.

Principle 2:

The "what" of learning

Multiple means of representation through recognition networks in the brain.

These strategies make for resourceful and knowledgeable learners.

- Offer clear, consistent, and relevant material, formatting, and messages.

- Vary the ways in which content is available (navigation, audio support, video, written material, images) and vary your examples.

- Share objectives, offer transitions between topics, and regularly summarize content to guide students.

Principle 3:

The "how" of learning

Multiple means of action and expression through strategic networks in the brain.

These strategies improve the learners’ strategic thinking and goal-setting skills.

- Guide the students’ goal-setting, course work planning, information management and progress monitoring.

- Vary types of learning tools, strategies, activities, and assessments.

- Offer a variety of ways for students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills.

These guidelines can be incorporated into current teaching methods without needing to start over. We can build on the way we currently teach, and adapt one step at a time.

Applying UDL does not require that educators abandon their adopted teaching and learning philosophies, theories, and models, such as cooperative learning, constructive learning, and (…) socio-cultural approaches to teaching and learning. (…) the mix of strategies they use (…) is welcoming to, accessible to, and usable by students with a wide variety of characteristics.

(Burgstahler, 2015, p. 42)

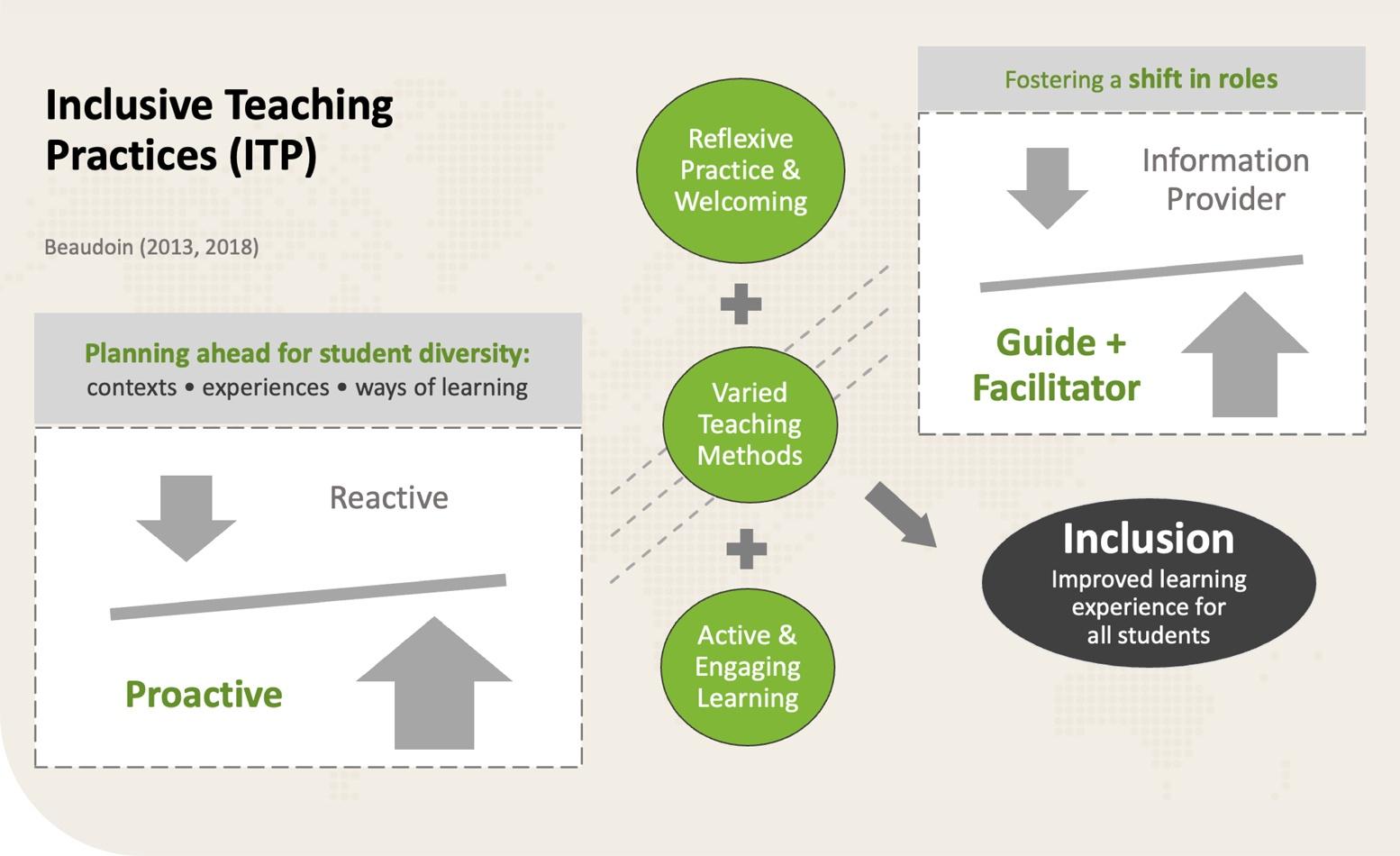

Inclusive teaching practices (ITP)

Beyond awareness, inclusive teaching involves first and foremost considering best practices in university teaching. A conceptual framework that describes an overview of Inclusive Teaching Practices (ITP) is provided below for illustration purposes.20

To teach inclusively, we suggest that courses be planned for a diverse range of students (remember diversity is the norm, not the exception), considering their varied contexts, their multiple experiences, and their diverse ways of learning. To that end, teachers must take a proactive approach that will see them reflect, conduct research, seek out information, and adapt as the weeks progress. ITP promote a change in the teacher’s role. From mere specialists who spew forth content, teachers become guides (or strengthen their role as guides) and facilitators in the learning process. Teachers must then build an inclusive learning atmosphere and environment, as well as an enriched experience for everyone by deliberately using reflexive and welcoming practices that are sensitive to students’ contexts, engaging and student-centred teaching methods, as well as active, experiential, authentic, and meaningful learning experiences for long-term learning.

In our view, the holistic perspective of ITP will prepare you for the inclusive strategies in education presented in Page 4 - Strategies and Tools. It will do this by providing structure to your reflections and experiences.

For ITP, we recommend the use of active, authentic, and engaging teaching methods as well as student-centred learning activities. Besides lectures, a variety of theories, frameworks, approaches, strategies and tools exist in the field of university pedagogy that are not only effective in supporting optimum learning, but are also inclusive. Such pedagogies are found in both Western culture and Indigenous culture.

In Western culture, inclusive pedagogies are based mostly on the principles of cognitive and social psychologies21 (process of collaboration, construction of meaning, and personal and professional transformation) to expand students’ views of the world. These pedagogies therefore seek to achieve a shared construction of knowledge through an awareness of contexts and phenomena, through critical analysis, and through relevant and engaging participatory action in which students take up challenges.

In other words, Western inclusive pedagogies are geared towards experiential, multi-perspective, active and group approaches that are centred around students, who are deemed stakeholders in pedagogic activity. Such approaches include inquiry-based learning, project-based approaches, case studies, simulations, and gamification. These methods work just as well in the sciences, the arts, the social sciences or in professional programs.

The pedagogical approaches promote the development of complex as well as critical thinking skills and reflection. They also support the coordination and development of resources, knowledge, and skills, such that these skills become more imbedded in the student’s ways of thinking and acting. The approaches are considered inclusive because they lead to discussion about the contexts, knowledge, and experiences of students from all walks of life. Space is made for them, they are listened to, their contribution is valued, they are given choices (topics, assessments), they are engaged in the learning process, and the development of their autonomy, their abilities and their sense of belonging is supported. In this way, students’ personal, social and academic success is promoted.

Furthermore, these approaches produce highly emotional learning experiences, not just cognitive or intellectual learning. Motivation, fears, self-esteem, confusion, frustration and enthusiasm affect individual learning ability. For example, if a person from a minority group does not feel included or secure in the classroom, or if they do not understand all the rules of the learning environment, they could drop out, fail or perform less well than their peers, especially those from majority groups. The impact is real and significant!

In conclusion

To summarize, teaching inclusively means putting students at the centre of the learning process. Consequently, we refer to a student-centric approach in an environment that takes the students’ contexts into account, makes room for them, gives them a voice, considers their previous knowledge and experiences, and includes active, varied and engaging activities. Besides enabling students to aim higher, this approach results in a transformative integration of the student’s knowledge from their personal, disciplinary and professional experiences, both cognitively and emotionally, and within their quest for meaning and learning by doing.

In that regard, how can we move beyond the status quo to truly open ourselves to a variety of teaching philosophies and practices and to various ways of learning; to be sensitive to culture and to be socially just; and to design and provide options that remove obstacles to learning, increase student retention, and promote academic success for all students?

By way of answer, we leave you with the thoughts expressed in this quote:

In the same way that you might consider creating coursework that anticipates the needs of all of the diverse types of learners in your room, examine how your coursework relates to, represents, and honors the cultural diversity within the students you teach. By using this as an overarching framework, you can ask yourself, “In what ways am I providing entry and connections into my coursework that speak to the diverse experiences of my learners?”

(Bass & Lawrence-Riddell, 2020, para. 4)

We now encourage you to go to Page 4 – Strategies and Tools for strategies to make your teaching as inclusive as possible.

Enjoy!

Document to download

- 1See: Gay, 2018; Krasnoff, 2016; Singhal and Gulati, 2020; Styres, 2017.

- 2See: Forstall Lemoine, 2019; Gay, 2018; Krasnoff, 2016 .

- 3Curiously, these four aspects overlap with the four main characteristics of good teachers: competence, kindness, passion, and eloquence. (TLSS, 2016, Communication Tips).

- 4See: Gay, 2018; Krasnoff, 2016; Mulnix, 2020; Singhal and Gulati, 2020.

- 5Biases emerge owing to our socialization context and the ensuing perception of the world. For example, are we equitable in how we assign the right to speak, in how we grade assignments (e.g., differing expectations) or in the permissions that we grant (e.g., deadlines)?

- 6See: Forstall Lemoine, 2019; Krasnoff, 2016; Singhal and Gulati, 2020.

- 7See: Adams and Bell, 2016; Carson-Byrde et al., 2019; Fox, 2018; Johnson, 2018; Sensoy and DiAngelo, 2017.

- 8For ease of reading, we have grouped the different critical theories and their concepts under the overarching expression “Social Justice in Education” (SJE), despite the risk of simplification and the lack of nuance that could result. Your suggestions and comments on this are welcome (for a future update).

- 9Even though we deliberately want to avoid making judgments or taking political stances, we still intend to move away from the status quo. That said, our primary concern is pedagogical, meaning that we are basically seeking to answer the following two questions: “How can we encourage the implementation of healthy, positive and safe learning environments to promote optimum learning for all of our students, regardless of which groups they belong to?” and “How can we minimize barriers to learning and equitably support the development of our students to their full potential and their academic success?”

- 10See:Adams and Bell, 2016.

- 11See: Sensoy and DiAngelo, 2017; Carson-Byrd et al., 2019.

- 12See: Adams and Bell, 2016; Sensoy and DiAngelo, 2017; Styres, 2017; Johnson, 2018; Tomlins-Jahnke et al., 2019; Tuhiwai Smith et al., 2019 .

- 13See: Adams and Bell, 2016; Styres, 2017; Carson-Byrd et al., 2019.

- 14See: Hooks, 1994; Jackson, 1999; Beasley, 2005; Nicholas and Baroud, 2015; Eddy et al., 2017; Mercado-Lopez, 2018; Silver, 2018.

- 15Almost by definition, successful academics thrived, as students, under traditional teaching methods. Thus, … faculty members will likely use teaching methods that worked well for them, although these methods may not work as well for a variety of students. (Yager, 2015, p. 309, as cited in Tobin & Behling, 2018, p. 131).

- 16See: Todd Rose in Steady, 2012; Burgstahler, 2015; Tobin and Behling, 2018; Carson-Byrd et al., 2019; Fritzgerald, 2020.

- 17See: Burgstahler and Cory, 2008; SASS-uOttawa, n.d.; Burgstahler, 2015; Tobin and Behling, 2018; Fritzgerald, 2020.

- 18See: Burgstahler and Cory, 2008; Burgstahler, 2015; Eyler, 2018; CAST, 2018; Tobin and Behling, 2018; Fritzgerald, 2020.

- 19See: CAST, 2018; Burgstahler, 2015; Tobin and Behling, 2018, p. 25; Fritzgerald, 2020.

- 20This framework, the product of a 2013 reflection on diversity and best practices in education, is still useful today for summarizing the inclusion process from a holistic perspective. That process brings together a series of critical topics that emerged from a literature review conducted prior to putting this website online; these topics are cited in the sections on CRT, SJE and UDL.

- 21See: Adams and Bell, 2016; Sensoy and DiAngelo, 2017; Gay, 2018; Krasnoff, 2016; Singhal and Gulati, 2020; Burgstahler, 2015; Tobin and Behling, 2018; Fritzgerald, 2020.

- 22See: Styres, 2017; Tomlins-Jahnke et al., 2019; Tuhiwai Smith et al., 2019; Swiftwolfe, 2019; The 8 Ways, 2021.

- 23Again, no political meaning should be ascribed to this term. “Movement” refers rather to the structure of this website and its browsing, both of which are the result of a conscious design decision. While others may have organized the content differently, we hope that our choices will not lead you away from the critical messages, which are: (1) to develop and teach classes in a more inclusive manner; and (2) to have the courage to broach difficult, but authentic, topics of conversation (with ourselves and with others) about why we teach the way we do, what impact our practices have on students, and how we can ensure that our teaching practices evolve. There is no question that we need to recognize and include Indigenous approaches.

- 24Circularity allows for dynamic synergic movement that is culturally responsive and emergent. Therefore, use of the circle and positioning concepts within circles provides a unifying concept that addresses the complex cultural and linguistic diversity of Indigenous peoples’ experiences and lived realities promoting the holistic well-being of community. (Styres, 2018, pp. 30–31).

- 25Journeying “must be characterized by purposeful intent – otherwise it is nothing more than aimless wandering. It is this purposeful intention that is transformative, leading the journeyer towards shifting previously held assumptions and paradigms”(Styres, 2018, p. 88). Journeying is a cycle. It will take time, beyond one course or one semester. It could be a life journey.

Social justice in education (SJE)

Social justice in education (SJE)7 and critical pedagogy, as well as concepts stemming from other critical theories,8 such as critical race theory, are interested in the inner workings of societal and institutional systems, as well as their impact on marginalized, minority, subordinate, and underrepresented groups. They are particularly concerned with the impact of these systems on individuals who, on a daily basis, are exposed to peer prejudice, discrimination, and systemic oppression, who are disadvantaged by privileges wittingly or unwittingly granted to dominant or majority groups, and who are subjected to inequitable practices that are often institutionalized. It is important that we examine these concepts because universities are a microcosm of general society.9

The inequalities and the power wielded by the majority or dominant group show themselves in the learning environment through racism, classism (systemic discrimination based on social and economic class), sexism, heterosexism, transphobia (systemic discrimination of trans* persons), ableism, ageism and systemic discrimination based on religion.

These attitudes, which are present on campus to varying degrees, affect the learning process and can compromise academic performance. Such unfavourable outcomes are generally caused by concerns related to

(Johnson, 2018, pp. 31–32)

Inequalities and power in the academic environment are also a reflection of general society. They permeate knowledge and disciplinary subjects, as well as teaching and learning support strategies in both official curricula (approved reference materials) and hidden curricula (implicit expectations, processes and goals, such as being able to write, communicate orally, work with others, and being able to contribute to society according to established standards). Such choices are not neutral. They are tainted by the values, beliefs, ideologies, norms and traditions of the dominant group. While they may seem logical, and therefore neutral, in the eyes of the majority, they are not for subordinate groups or for individuals who belong to one or more of these groups.

(Johnson, 2018, p. 107)

The core principles of SJE are based in part on the principles of critical pedagogy and critical theory. SJE is concerned with the education of all learners through awareness, critical reflection, dialogue, and mobilization (experiential learning). It seeks to bring about significant and lasting change to how we teach and support learning. The goal is to provide learning environments and experiences that are as inclusive as possible. This approach promotes democracy and puts students at the centre of authentic experiences.