Context and considerations

In this page, you will find information about diversity and inclusion, statistics, a series of questions, resources to uncover biases, and tips on how to become an ally. It will get you started on the road to a more inclusive teaching practice.

Teaching inclusively – How to get started

To pique your curiosity about the contents of this tab, we have two questions for you:

The first is a broad one: How do our experiences and upbringing, as well as our view of the world in general and of teaching in particular, impact how we teach?

The second is more specific: How do those factors influence, for example, how we design courses, disseminate content, conduct learning activities, answer questions, grade assignments, and interact by email or synchronously with the students enrolled in our courses?

According to numerous sources, answering those questions is the first step towards inclusive teaching.

As we will see in Page 3 – Conceptual Frameworks, our traditional teaching methods do not work with everyone. They create generally unintended inequities, thereby affecting our students’ success.

So how can we adapt our teaching methods and promote learning to effectively and equitably support as many students as possible?

We will answer this question in Page 4 – Strategies and Tools.

Did you know?

For the most part, instructors at higher education institutions are not trained to teach. (…) Many college instructors tend to teach in the way that they were taught or in a manner with which they are most comfortable.

(Tobin & Behling, 2018, p. 35)

Almost by definition, successful academics thrived, as students, under traditional teaching methods. Thus, … faculty members will likely use teaching methods that worked well for them, although these methods may not work as well for a variety of students.

(Yager, 2015, p. 309, as cited in Tobin & Behling, 2018, p. 131)

Eight observations

Let's now take a look at a few observations, statistics and considerations on academic diversity and inclusion.

Diversity is the norm, not the exception.

Students do not form a monolithic group. The “average learner” is a myth. As Todd Rose states1, the fields of neuroscience and pedagogy confirm that connections that are made in the brain differ from one person to another, impacting learning. If we add the influence of different environments to the mix, it is especially important that we consider the normalization of diversity in how we teach and support learning2.

In the 1990s, research in neurosciences found that (…) variability is the norm: no two students learn alike, regardless of ability.

(Tobin & Behling, 2018, p. 24)

As we will see in Page 3-Conceptual Frameworks and Page 4-Strategies and Tools, having students participate actively, varying the kinds of activities/examples/resources, and offering a variety of assessment methods can, among other approaches, optimize the learning experience-which will, you will recall, help reduce barriers to learning and support the academic success of every student.

Teaching with inclusion in mind requires work.3

Work to uncover our unconscious biases. Work to open our mind to new ways of seeing the world around us. Work to learn about the different groups that make up our courses. Work to review and adapt our courses. Work to give a voice to marginalized students in the classroom (we will see what this means later). Work to collect feedback, reflect, and adjust. Work: over and over again.

The good news is that we are here to help you! This website has plenty of tips and strategies, and there are also many resources on the Internet you can turn to for guidance. Remember that teaching inclusively reduces barriers to learning, strongly affects student success, and increases student retention rates.

Tip: Start from where you are now to gradually get to where you want to be or should be. It’s a process. A long-term one.

Members of marginalized groups are underrepresented in academic settings

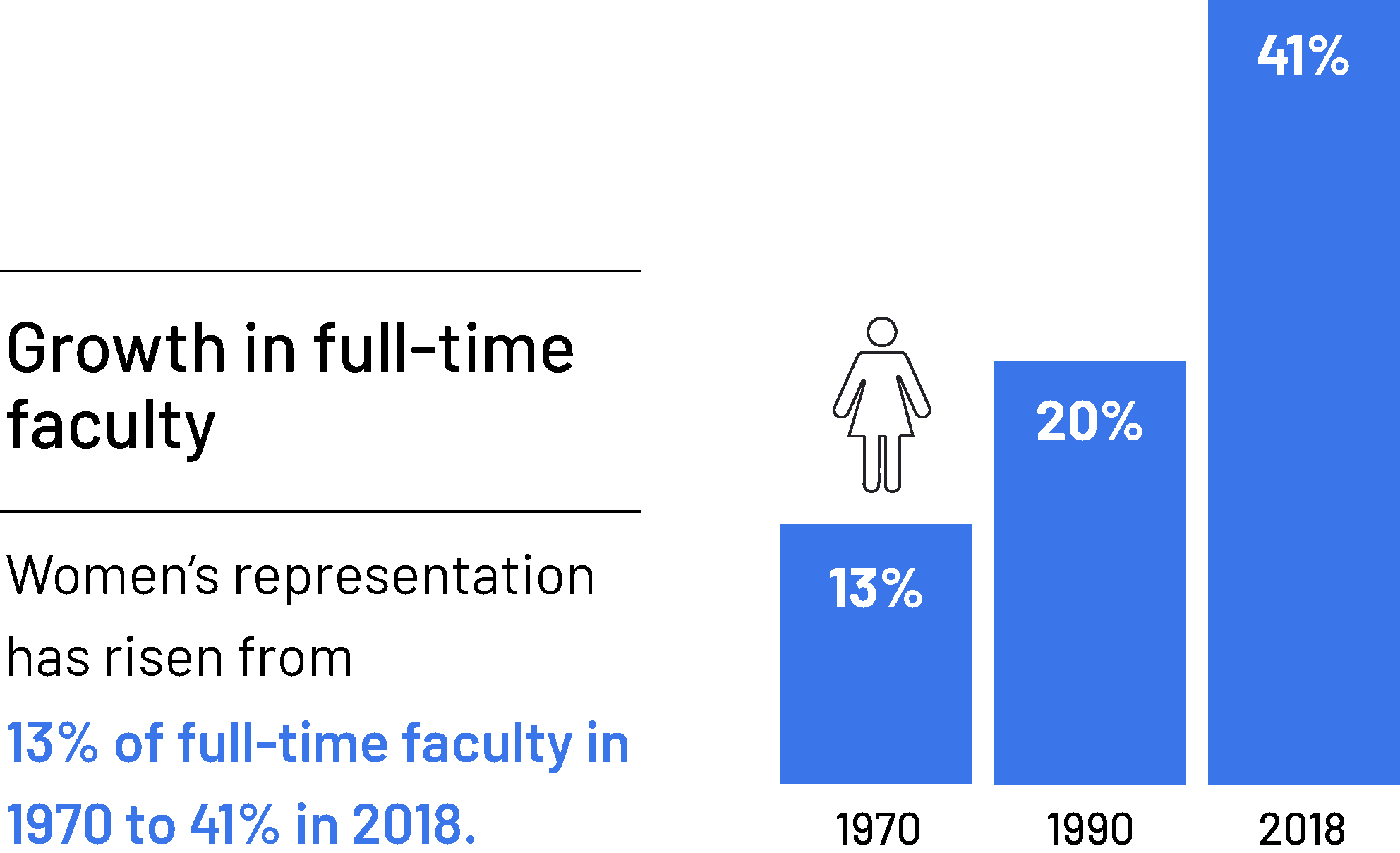

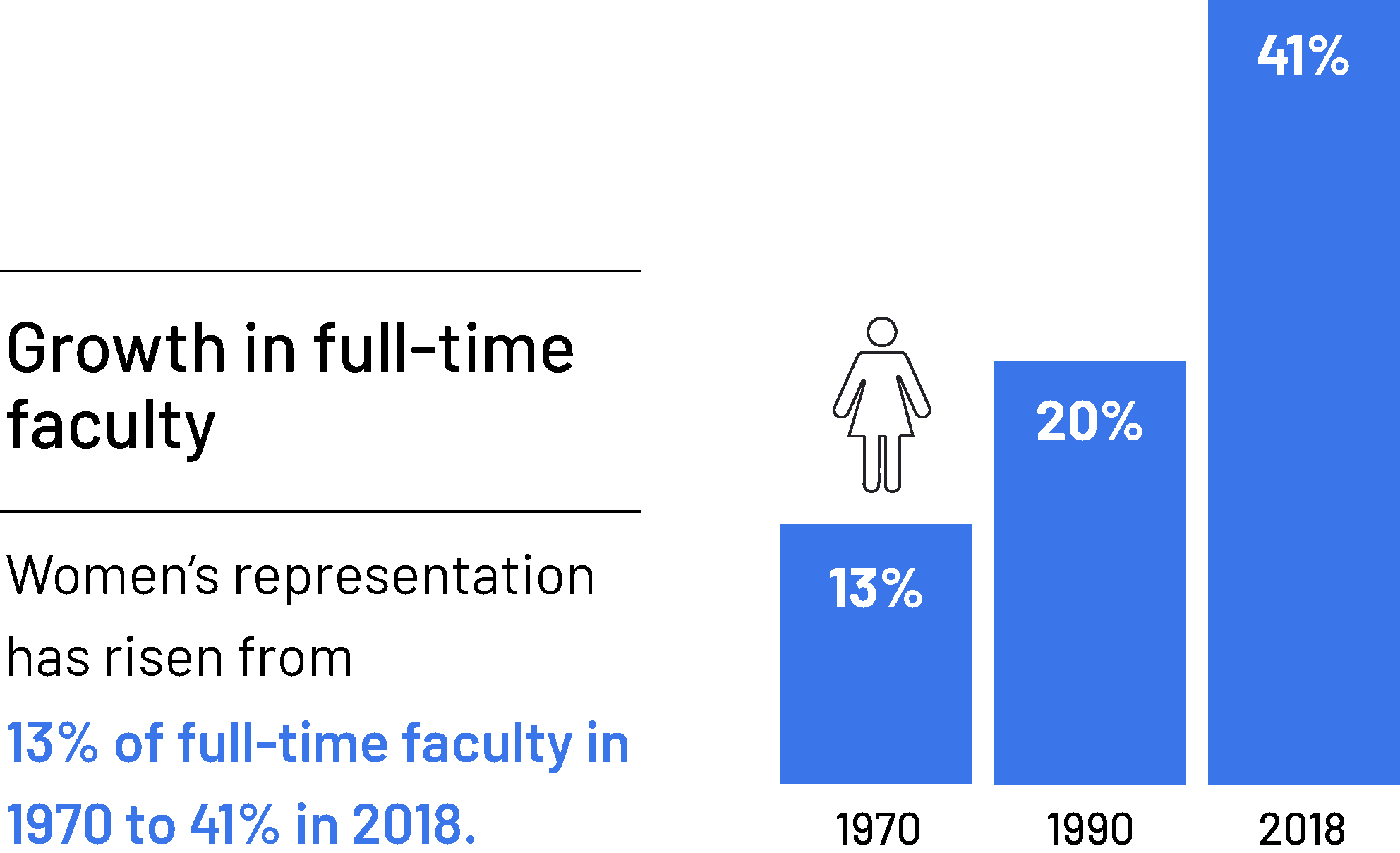

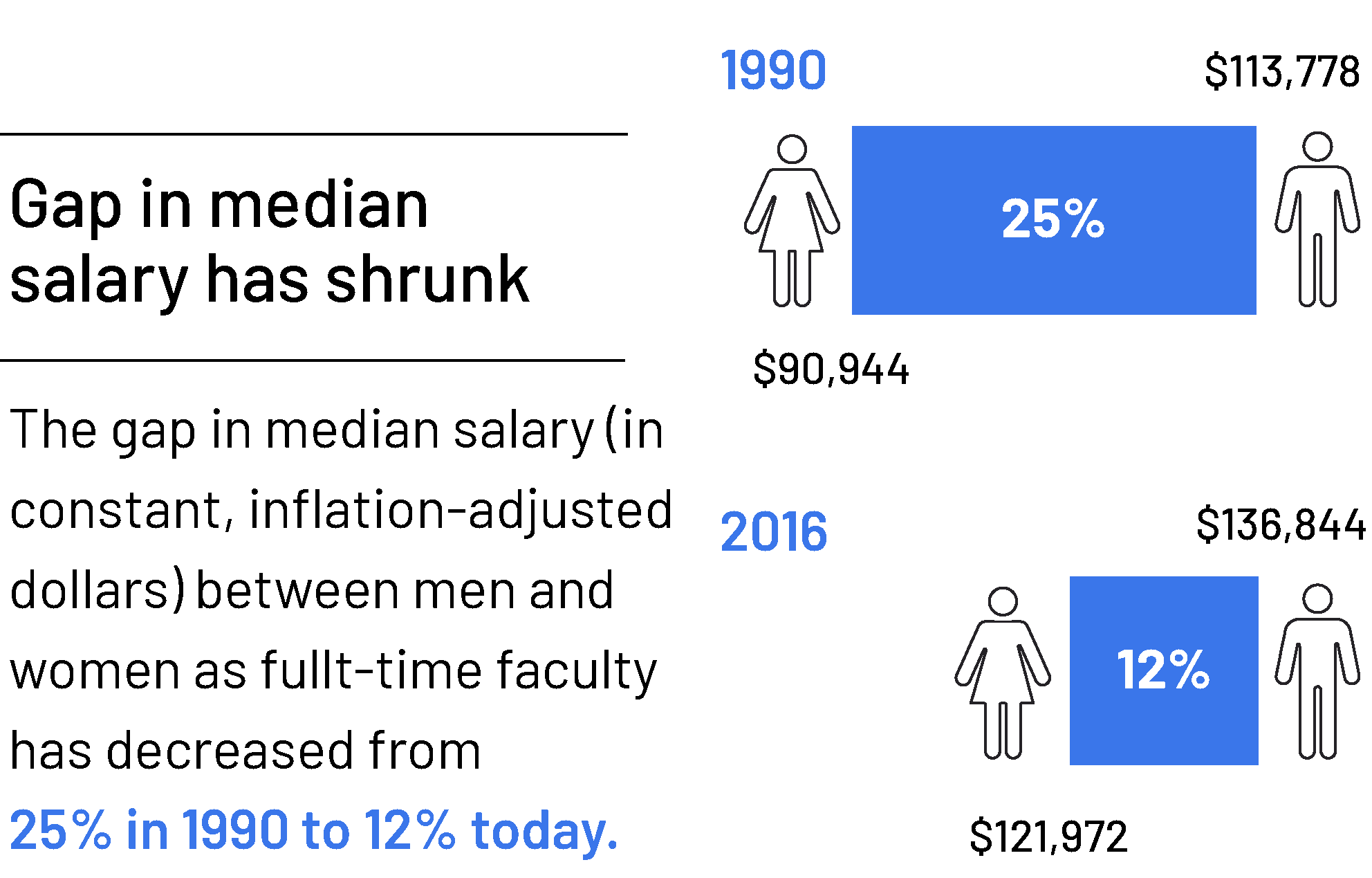

Although we note significant improvements in wage and hiring parity between men and women over the past 30 years (see Figure 1), the male-female ratio of regular faculty in Canadian universities is still predominantly male (60%). However, women outnumber men in the student population at both the undergraduate and graduate levels.

The University of Ottawa is no exception to this rule: in 2019, there were 40.8% regular female faculty members versus 59.2% regular male faculty members.4 These proportions were inverted in the student population, which consisted of 41% male students versus 59% female students at all levels for the same period.5

Figure 1 - Source: Universities Canada, 2021.

This phenomenon also affects senior management in universities, where racialized individuals are substantively underrepresented, according to a 2019 survey of 88 Canadian universities by Universities Canada. Racialized individuals, who account for 22% of the general population in Canada, 40% of the student population, and 21% of Canadian university faculty, hold just 8% of the senior leader positions (see Figure 2).

|

Women |

Racialized |

Indigenous |

Persons with |

LGBT2S+ |

Identifies with | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Senior university |

48.9 |

8.3 |

2.9 |

4.5 |

8.0 |

10.7 |

|

Full-time faculty2 |

40.2 |

20.9 |

1.3 |

21.83 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Doctorate holders4 |

37.5 |

30.5 |

0.9 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Graduate students5 |

54.8 |

40.18 |

3.3 |

5.0 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Undergraduate student6 |

57.1 |

40.08 |

3.0 |

22.0 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

General population7 |

50.9 |

22.3 |

4.9 |

22.33 |

3.09 |

N/A |

|

||||||

Figure 2 - Source: table adapted from Universities Canada (2019).

At the University of Ottawa, where data on racialized individuals are just beginning to be collected, the percentage of racialized individuals on campus would be expected to sit between 25% and 30% to reflect the city and province percentages.6 That figure is based on the 2016 Census,7 which found that visible minorities accounted for 26.3% of Ottawa’s population and from the projection that by 2036, 36% of Ontario’s population will consist of people from immigrant backgrounds.8

Did you know?

People who belong to one or more marginalized groups are not necessarily visible. Besides people of colour or students who use wheelchairs to get around, many marginalized individuals in your classes go unnoticed. Examples include students with learning disorders, people whose mother tongue is other than French or English, students whose beliefs are different from those of the majority, people who do not fit social class stereotypes, and LGBTQ2S+ students.

People with a disability account for barely 5% of senior leaders in Canadian universities, whereas they comprise 22% of the Canadian and faculty member population and approximately 28% of the student population. In addition, while the proportion of people living with a disability at the undergraduate level (22%) is similar to that of the general population, they account for just 5% of students at the graduate level (see Figure 2).

Indigenous Peoples, who comprise nearly 5% of the Canadian population, account for less than 1% of Ph.D. holders, resulting in significant underrepresentation among academic faculty, holding less than 1.5% of all regular positions.9 At the University of Ottawa,10 as in all Canadian universities (see Figure 2), data from 2019 shows that students with Indigenous ancestry account for just 3% of the undergraduate population. This situation will only improve if this population, of which 27% comprises young people under 14, continues to have fewer opportunities to pursue post-secondary education than the non-Indigenous population.11

These are just a few examples of various marginalized groups on campuses, illustrating the work that remains (e.g., data gathering) to make universities more inclusive and representative of the Canadian population.

Why should I become more inclusive in my teaching?

There are a lot of biases, microaggressions, disadvantages and invisibility challenges influencing what is going on in the learning environment.

It seems that most of us see the forest, not the trees, or only a few when we do...when we think of the students that make up our classrooms.

In order to make our teaching more inclusive, we must first recognize that the way we teach is influenced by implicit rules, systemic processes, and ideologies, which, more often than not, have been shaped by the power, influence, and privilege historically held by the white Eurocentric majority group in Canadian society, and in universities. With this in mind, we must then acknowledge that the way we teach may disadvantage some students.

As an educational institution, the university has normalized the experience of students who are white, young, cismale, heterosexual, middle-to-upper class, lacking disabilities, and without children. If a student deviates from these categories, they are more likely to experience oppressive obstructions in the completion of their degree. (…) Recognizing that education privileges certain groups over others, processes of unlearning require an engagement with ideas, narratives, and theories that counter the norm.

(Tuhiwai Smith et al., 2019, p. 167)

Did you know?

Several studies describe the individual as being composed of not one but many attributes or characteristics that make up their identity. One can be privileged as a white person, but less so when having a disability, or when being a woman (in STEM for example). This is called intersectionality. The following identity intersection matrix (figure 3) provides an overview of various identities (race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, age, ability) intersecting with one another, and the planes on which oppression may occur (personal, community, or systemic).12

Figure 3 - Source: Adams et Zúñiga, 2016, p. 112

Students from marginalized groups often feel like they aren’t good enough, are being pushed aside, are being treated unfairly, and are experiencing microaggressions on a daily basis

Inclusive teaching means fully acknowledging this reality individually and collectively, acknowledging and accepting different contexts, and making space for every student to be safely heard in the classroom. This reality, which can harden students' experience on campus and in society, also explains the lower retention rates among marginalized students.13

But I am not a racist! I am not homophobic! I am all for gender equality! We are all humans, after all.

Interesting fact: it would appear that this ‘‘we are all human’’ notion is more often expressed by the people in the majority group, largely because they do not face discrimination or microaggressions on a daily basis. As for race colour blindness – that is, to see individuals as humans rather than as people of colour – may seem positive at first take, but it’s not. It supports the status quo.14

All of this to say we still have a lot of work to do to make our classrooms truly inclusive.

Want to read more about the student experience of marginalized groups?

See the document: Student Testimonials - Quotes

Professors are agents of change for inclusion and integration15

Since faculty members are in direct contact with the student population, they play an important role in making each student feel welcome. Faculty members must create a positive, respectful and safe environment to encourage everyone to take part in learning activities and community life. Strategies for creating such learning environments are presented in Page 4 - Strategies and Tools.

Here are some questions to consider with regard to learning environments:

- How can we make all students feel welcome and part of the learning community? How can we make them feel supported in their quest to learn and graduate?

- How will I use my authority as an instructor to connect with students and make everyone feel comfortable? Who may feel comfortable, or uncomfortable, in my presence? At what point does the discomfort needed for good pedagogy transition into something else? (Carson-Byrd et al., 2019)

TESTIMONIAL

As professors we have a certain amount of power in the classroom. We should use our power to enforce rules of behavior, to let students know very clearly the ways they can interact with each other. They have to act decently, politely, with some degree of sensitivity, even if it is forced or fake at first. The important thing is to establish an atmosphere of respect that is safe for everyone. Call it political correctness if you want. I call it basic human decency.

(Fox, 2018, p. 28)

As members of the teaching staff, we do hold a lot of power over students as well as many responsibilities with respect to their learning experience and academic success. Research underscores the need for reflection when trying to achieve the best possible outcomes…

How can we ensure that all students (…) have authentic, meaningful experiences to build knowledge, make choices about their learning, connect with (the material), and share their strengths (with others)?

(Fritzgerald, 2020, p. 29)

Did You Know?

About emotions and learning:

A simple affirmation of learners' positive sense of self, of their value as individuals, and the importance of their membership in a cultural tradition has repeatedly been shown to have positive effects on learning and on performance.

(Meyer et al., 2014, p. 57, as cited in Fritzgerald, 2020, p. 95)

Similarly, Eyler (2018) speaks to the idea of the “danger of stereotypes”: when studying, if you think you are not good enough and that you will fail the test, you are more likely to fail. This type of self-fulfilling prophecy is linked to marginalized groups and the stereotypes that teachers hold about their students.

Thinking about the way we teach, and why we teach this way

It is necessary to reflect on our ways of being, and doing, as teachers.

Our way of interacting is determined by our own experience, particularly by our socialization habits and our upbringing. We go into the classroom with our own view of the world (known as ethnocentrism). Therefore, to teach in an inclusive way, we must consider not only the context of a variety of other people16, but also our own context (our values, beliefs, perceptions, biases, prejudices, etc.) both personally and professionally; in terms of our field or discipline; and in terms of our place in the academic arena. We need to reflect on our role, on the power we hold and the privileges we benefit from, and we need to remind ourselves that not everyone has the same experience, or comes from the same background, as we do.17

Everyone has biases, both recognized and unrecognized. Like our students, we have internalized assumptions and stereotypes about our own and other social groups through socialization and societal conditioning. We need to recognize that none of us stand outside of or above the systems we study, and that our perspectives are inevitably partial and shaped by our social locations.

(Adams & Bell, 2016, p. 403)

Many studies suggest questions to guide our efforts to become inclusive.

There are so many questions that we could select only a few. Take a moment, or a few hours, to read them, think about them, discuss them and answer them as honestly as possible. Then, think about how what you have uncovered will affect the way you prepare your courses and teach them, including how you will interact with all your students, and how they will interact with one another in front of you, and when away from you.

Warning

You may feel uncomfortable answering some of the following questions. Any growth (personal and/or professional) needs to generate an imbalance in order for a shift to occur. This requires conscious effort, regularly rethinking our positions, as well as managing feelings or ideas that we may not be used to. The effects can feel similar to feelings experienced during change management or reflective practice. What is happening and why? What went well? What didn’t go so well? Why? What can I do next time so that it goes better?

Go at your own pace! Be courageous and be authentic, but don’t be too hard on yourself. Always take care of yourself. Talk to people around you. You are not alone in thinking about how to be more inclusive and how to teach more inclusively.

Finally, you may feel some resistance, but be aware that this is not unusual.

When confronted with evidence of inequality that challenges our identities, we often respond with resistance; we want to deflect this unsettling information and protect a worldview that is more familiar and comforting.

(Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017, p. 1)

Forms that resistance can take include silence, withdrawal, immobilizing guilt, feeling overly hopeless or overly hopeful, rejection, anger, sarcasm, and argumentation. These reactions are not surprising because mainstream narratives reinforce the idea that society is overall fair, and that all we need to overcome injustice is to be nice and treat everyone the same.

(Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017, p. 2)

If these emotions surface as you are reading, feel free to take a break and come back to it later.

Eight Observations

Let's now take a look at a few observations, statistics and considerations on academic diversity and inclusion.

First observation

Diversity is the norm, not the exception.

Students do not form a monolithic group. The “average learner” is a myth. As Todd Rose states1, the fields of neuroscience and pedagogy confirm that connections that are made in the brain differ from one person to another, impacting learning. If we add the influence of different environments to the mix, it is especially important that we consider the normalization of diversity in how we teach and support learning.2

In the 1990s, research in neurosciences found that (…) variability is the norm: no two students learn alike, regardless of ability.

(Tobin et Behling, 2018, p. 24)

As we will see in Page 3-Conceptual Frameworks and Page 4-Strategies and Tools, having students participate actively, varying the kinds of activities/examples/resources, and offering a variety of assessment methods can, among other approaches, optimize the learning experience-which will, you will recall, help reduce barriers to learning and support the academic success of every student.

Second observation

Enseigner en pensant à l’inclusion demande un certain travail3.

Work to uncover our unconscious biases. Work to open our mind to new ways of seeing the world around us. Work to learn about the different groups that make up our courses. Work to review and adapt our courses. Work to give a voice to marginalized students in the classroom (we will see what this means later). Work to collect feedback, reflect, and adjust. Work: over and over again.

The good news is that we are here to help you! This website has plenty of tips and strategies, and there are also many resources on the Internet you can turn to for guidance. Remember that teaching inclusively reduces barriers to learning, strongly affects student success, and increases student retention rates.

Tip: Start from where you are now to gradually get to where you want to be or should be. It’s a process. A long-term one.

Third observation

Members of marginalized groups are underrepresented in academic settings.

Although we note significant improvements in wage and hiring parity between men and women over the past 30 years (see Figure 1), the male-female ratio of regular faculty in Canadian universities is still predominantly male (60%). However, women outnumber men in the student population at both the undergraduate and graduate levels.

The University of Ottawa is no exception to this rule: in 2019, there were 40.8% regular female faculty members versus 59.2% regular male faculty members.4 These proportions were inverted in the student population, which consisted of 41% male students versus 59% female students at all levels for the same period.5

Figure 1 - Source: Universities Canada, 2021.

This phenomenon also affects senior management in universities, where racialized individuals are substantively underrepresented, according to a 2019 survey of 88 Canadian universities by Universities Canada. Racialized individuals, who account for 22% of the general population in Canada, 40% of the student population, and 21% of Canadian university faculty, hold just 8% of the senior leader positions (see Figure 2).

| Women (%) | Racialized (%) | Indigenous (%) | Persons with disabilities (%) | LGBT2S+ (%) | Identifies with two or more designated groups (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senior university leaders1 |

48.9 | 8.3 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 8.0 | 10.7 |

| Full-time faculty2 | 40.2 | 20.9 | 1.3 | 21.83 | N/A | N/A |

| Doctorate holders4 | 37.5 | 30.5 | 0.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Graduate students5 | 54.8 | 40.18 | 3.3 | 5.0 | N/A | N/A |

| Undergraduate student6 | 57.1 | 40.08 | 3.0 | 22.0 | N/A | N/A |

| General population7 | 50.9 | 22.3 | 4.9 | 22.33 | 3.09 | N/A |

|

||||||

Figure 2 - Source: table adapted from Universities Canada (2019).

At the University of Ottawa, where data on racialized individuals are just beginning to be collected, the percentage of racialized individuals on campus would be expected to sit between 25% and 30% to reflect the city and province percentages.6 That figure is based on the 2016 Census,7 which found that visible minorities accounted for 26.3% of Ottawa’s population and from the projection that by 2036, 36% of Ontario’s population will consist of people from immigrant backgrounds.8

Did you know?

People who belong to one or more marginalized groups are not necessarily visible. Besides people of colour or students who use wheelchairs to get around, many marginalized individuals in your classes go unnoticed. Examples include students with learning disorders, people whose mother tongue is other than French or English, students whose beliefs are different from those of the majority, people who do not fit social class stereotypes, and LGBTQ2S+ students.

People with a disability account for barely 5% of senior leaders in Canadian universities, whereas they make up 22% of the Canadian and faculty member population, and approximately 28% of the student population. In addition, while the proportion of people living with a disability at the undergraduate level (22%) is similar to that of the general population, they account for just 5% of students at the graduate level (see Figure 2).

Indigenous Peoples, who make up close to 5% of the Canadian population, account for less than 1% of PhD holders, resulting in significant underrepresentation among academic faculty, where they hold less than 1.5% of all regular positions.9 At the University of Ottawa,10 as in all Canadian universities (see Figure 2), data from 2019 shows that students with Indigenous ancestry account for just 3% of the undergraduate population. This situation will not improve as long as this population, of which 27% is made up of young people under the age of 14, continues to have fewer opportunities to pursue a post-secondary education than the non-Indigenous population.11

These are just a few examples of the presence of various marginalized groups on campuses, illustrating the work that remains to be done (e.g., data gathering) to make universities more inclusive and representative of the Canadian population.

Why Should I Become More Inclusive in my Teaching?

Fourth observation

There are a lot of biases, microaggressions, disadvantages and invisibility challenges influencing what is going on in the learning environment.

It seems that most of us see the forest, not the trees, or only a few when we do... when we think of the students that make up our classrooms.

In order to make our teaching more inclusive, we must first recognize that the way we teach is influenced by implicit rules, systemic processes, and ideologies, which, more often than not, have been shaped by the power, influence, and privilege historically held by the white Eurocentric majority group in Canadian society, and in universities. With this in mind, we must then acknowledge that the way we teach may disadvantage some students.

As an educational institution, the university has normalized the experience of students who are white, young, cismale, heterosexual, middle-to-upper class, lacking disabilities, and without children. If a student deviates from these categories, they are more likely to experience oppressive obstructions in the completion of their degree. (…) Recognizing that education privileges certain groups over others, processes of unlearning require an engagement with ideas, narratives, and theories that counter the norm.

(Tuhiwai Smith et coll., 2019, p. 167)

Did You Know?

Several studies describe the individual as being composed of not one but many attributes or characteristics that make up their identity. One can be privileged as a white person, but less so when having a disability, or when being a woman (in STEM for example). This is called intersectionality. The following identity intersection matrix (figure 3) provides an overview of various identities (race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, age, ability) intersecting with one another, and the planes on which oppression may occur (personal, community, or systemic).12.

Figure 3 - source : Adams and Zúñiga, 2016, p. 112

Fifth observation

Students from marginalized groups often feel like they aren’t good enough, are being pushed aside, are being treated unfairly, and are experiencing microaggressions on a daily basis.

Inclusive teaching means fully acknowledging this reality, both individually and collectively, acknowledging and accepting different contexts, and making space for every student to be safely heard in the classroom. This reality, which can harden students' experience on campus and in society, also explains the lower retention rates among marginalized students.13

But, I am not a racist! I am not homophobic! I am all for gender equality! We are all humans after all.

Interesting fact: it would appear that this ‘‘we are all human’’ notion is more often expressed by the people in the majority group, largely because they do not face discrimination or microaggressions on a daily basis. As for race, colour blindness-that is, to see individuals as humans rather than as people of colour-may seem positive at first take, but it’s not. It supports the status quo.14

All of this to say we still have a lot of work to do to make our classrooms truly inclusive.

Want to read more about the student experience of marginalized groups?

See : Student Testimonials - Quotes - Document to download

Sixth observation

Teachers are agents of change for inclusion and integration.15

Since faculty members are in direct contact with the student population, they play an important role in making each student feel welcome. Faculty members must create a positive, respectful and safe environment to encourage everyone to take part in learning activities and community life. Strategies for creating such learning environments are presented in Page 4 - Strategies and Tools.

Here are some questions to consider with regard to learning environments:

- How can we make all students feel welcome and part of the learning community? How can we make them feel supported in their quest to learn and graduate?

- How will I use my authority as an instructor to connect with students and make everyone feel comfortable? Who may feel comfortable, or uncomfortable, in my presence? At what point does the discomfort needed for good pedagogy transition into something else? (Carson-Byrd et al., 2019)

TESTIMONIAL

As professors we have a certain amount of power in the classroom. We should use our power to enforce rules of behavior, to let students know very clearly the ways they can interact with each other. They have to act decently, politely, with some degree of sensitivity, even if it is forced or fake at first. The important thing is to establish an atmosphere of respect that is safe for everyone. Call it political correctness if you want. I call it basic human decency.

(Fox, 2018, p. 28,)

As members of the teaching staff, we do hold a lot of power over students as well as many responsibilities with respect to their learning experience and academic success. Research underscores the need for reflection when trying to achieve the best possible outcomes…

How can we ensure that all students (…) have authentic, meaningful experiences to build knowledge, make choices about their learning, connect with (the material), and share their strengths (with others)?

(Fritzgerald, 2020, p. 29, notre traduction)

Dis you know?

About emotions and learning:

A simple affirmation of learners positive sense of self, of their value as individuals, and the importance of their membership in a cultural tradition has repeatedly been shown to have positive effects on learning and on performance.

(Meyer et al., 2014, p. 57, as cited in Fritzgerald, 2020, p. 95)

Similarly, Eyler (2018) speaks to the idea of the “danger of stereotypes”: when studying, if you think you are not good enough and that you will fail the test, you are more likely to fail. This type of self-fulfilling prophecy is linked to marginalized groups and the stereotypes that teachers hold about their students.

Thinking about the way we teach, and why we teach this way

Seventh observation

It is necessary to reflect on our ways of being, and doing, as teachers.

Our way of interacting is determined by our own experience, particularly by our socialization habits and our upbringing. We go into the classroom with our own view of the world (known as ethnocentrism). Therefore, to teach in an inclusive way, we must consider not only the context of a variety of other people16, but also our own context (our values, beliefs, perceptions, biases, prejudices, etc.) both personally and professionally; in terms of our field or discipline; and in terms of our place in the academic arena. We need to reflect on our role, on the power we hold and the privileges we benefit from, and we need to remind ourselves that not everyone has the same experience, or comes from the same background, as we do.17

Everyone has biases, both recognized and unrecognized. Like our students, we have internalized assumptions and stereotypes about our own and other social groups through socialization and societal conditioning. We need to recognize that none of us stand outside of or above the systems we study, and that our perspectives are inevitably partial and shaped by our social locations.

(Adams et Bell, 2016, p. 403, notre traduction)

Eight observation

Many studies suggest questions to guide our efforts to become inclusive.

There are so many questions that we could select only a few. Take a moment, or a few hours, to read them, think about them, discuss them and answer them as honestly as possible. Then, think about how what you have uncovered will affect the way you prepare your courses and teach them, including how you will interact with all your students, and how they will interact with one another in front of you, and when away from you.

Warning

You may feel uncomfortable answering some of the following questions. Any growth (personal and/or professional) needs to generate an imbalance in order for a shift to occur. This requires conscious effort, regularly rethinking our positions, as well as managing feelings or ideas that we may not be used to. The effects can feel similar to feelings experienced during change management or reflective practice. What is happening and why? What went well? What didn’t go so well? Why? What can I do next time so that it goes better?

Go at your own pace! Be courageous and be authentic, but don’t be too hard on yourself. Always take care of yourself. Talk to people around you. You are not alone in thinking about how to be more inclusive and how to teach more inclusively.

Finally, you may feel some resistance, but be aware that this is not unusual.

When confronted with evidence of inequality that challenges our identities, we often respond with resistance; we want to deflect this unsettling information and protect a worldview that is more familiar and comforting.

(Sensoy et DiAngelo, 2017, p. 1)

Forms that resistance can take include silence, withdrawal, immobilizing guilt, feeling overly hopeless or overly hopeful, rejection, anger, sarcasm, and argumentation. These reactions are not surprising because mainstream narratives reinforce the idea that society is overall fair, and that all we need to overcome injustice is to be nice and treat everyone the same.

(Sensoy et DiAngelo, 2017, p. 2)

If these emotions surface as you are reading, feel free to take a break and come back to it later.

Questions to reflect on one’s practice

- How did the way I was raised and socialized (family, group of friends, schooling, religious institutions, etc.) impact how I perceive and act toward people who are different from the norm or the majority, or from what I believe in? How does this affect how I design and deliver courses, how I interact with students and treat them in my course(s)?18

- How do I perceive and act towards people who are different from me, from the norm? Where does this come from?

- What effect does it have on my course design and delivery, and my interactions with students, TAs, colleagues and staff?

- What would I like to change or try in my course design and delivery, and in my student interactions?

To help you answer the question about your socialization (where your thinking and behaviours come from), we encourage you to read the following testimonial:

TESTIMONIAL

I’m white, as far as I know. But I was never explicitly told I was white, so how do I know it? That’s a mystery. I can think of subtle ways that whites in my neighborhood (family, group of friends, school or work environment) defined themselves and each other as white. There were ways of teasing and insinuating that someone (was different). It was obvious from the tone of voice that this was something shameful, something to be avoided. (…) “They” were mysterious, different, and somehow dangerous. So I think I learned what race (the majority; gender, sexual orientation, etc.) was by understanding what I was not.

(Fox, 2018, p. 121).

Note: If you are not from what could be understood as the majority group (you do not consider yourself white, you are not a male, you are not heterosexual, you are not abled bodied or you are not a Christian), feel free to adapt this testimonial to your context. What does this show? And how does it influence the way you teach?

To explore further, we suggest that you look at the following set of questions from Twyman-Ghoshal & Carkin Lacorazza (2021). We hope it will help guide your analysis and reflection on becoming a more inclusive instructor and creating a learning environment that suits everyone. You can also browse through Page 4 – Strategies and Tools to find resources to help you answer some of these questions and achieve your goals.

Document to download

- “How does your social and geographical location influence your identity, knowledge, and accumulated wisdom?” “What knowledge are you missing?”

- “What privileges and power do you hold?” “How do you exercise your power and privilege?”

- “How do your power and privilege show up in your (teaching)?”

- “How do your biases and privileges take up space and silence others?” (Twyman-Ghoshal and Carkin Lacorazza, 2021)h et.

Congratulations for considering these questions, reflecting on them and answering them. Now...

Did you know?

Excellence in teaching dovetails well with inclusive pedagogies: competence in terms of knowledge and experience, desire to see students succeed, passion for the field, and good communication are key. Similarly, a good teacher is well prepared, is a good role model, makes expectations clear, is approachable, gets to know students, respects students and maintains privacy, does not make assumptions about a student’s capabilities, encourages students, is patient, challenges students, helps students apply knowledge, is open to new ideas, is enthusiastic, facilitates the exchange of ideas between students and between teacher and students, and adjusts to the unique needs of students.

(Burgstahler, 2015, p. 49)

Where do I go from here?

Now that you have reflected on many questions, you are at a crossroad. At this point, you could:

- Explore further by using the resources below.

- Learn more about becoming an ally in your own classroom and beyond by clicking on How to become an ally (or be a better one)?

- Head over to Page 3 – Conceptual Frameworks to learn more about some of the theoretical foundations of inclusive teaching (key concepts).

- Go to Page 4 – Strategies and Tools to discover the many different strategies available to you.

Which resources can help me reflect on my unconscious biases?

The following resources will provide guidance should you wish to explore the topic of unconscious biases in more detail:

Benton Kearny, D. (2022). Universal Design for Learning (UDL) for Inclusivity, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility (IDEA): A Guide for Post-Secondary Educators. e-CampusOntario.

Note: Refer to sub-module 4.3: Uncovering Unconscious Bias.

Nordell, J. (2021). The End of Bias: A Beginning: The Science and Practice of Overcoming Unconscious Bias. Metropolitan Books.

Reshamwala, S. (2016). “Who, me? Biased?” New York Times. (video series).

Note: This simple, well-explained series provides good explanations and strategies for tackling biases.

Khan Academy. Perception, Prejudice and Bias Questions.

Note: This site offers a series of questions and interesting videos about biases, prejudices and ways we stereotype others.

How to become an ally (or be a better one)?

Below are three questions and answers to help you understand the definition of an ally, the role of an ally, and how to be an ally.

In general, being an ally means: Validating and supporting people who are socially or institutionally minoritized in relation to you, regardless of whether you completely agree with or understand where they are coming from; Engaging in continual self-reflection to uncover your socialized privilege and internalized superiority; (…) Advocating when the oppressed group is absent by challenging misconceptions; Letting go of control and sharing power when possible; Taking risks to build relationships with minoritized group members; (…) Having humility and willingness to admit not knowing; Earning trust through action.

(Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017, p. 211)

In a nutshell

The DO's

Listen to the experts

Ask what you can do

Build relationships based on mutual consent & trust

Research to learn more about the history

Continue to support & act in meaningful ways

Figure 4 - Source: Swiftwolfe (2019)

In conclusion

In this page, you have learned about inclusive teaching and its benefits. You have familiarized yourself with a lot of data, questions, resources and strategies that will help you become an ally in your classroom.

In Page 3 – Conceptual Frameworks, you will learn more about the key fundamentals of inclusive teaching.

Document to download

1See: Steady, 2012.

2See the authors cited in “Universal Design for Learning (UDL)” in Page 3.

3See: Adams & Bell, 2016; Fox, 2018; Fritzgerald, 2020; Swiftwolfe, 2019; Twyman-Ghoshal & Carkin Lacorazza, 2021.

4See: University of Ottawa, 2021a.

5See: University of Ottawa, 2021b.

6See: Ontario’s Universities, 2021, p. 1

7See: Statistics Canada, 2017.

8See: Ontario’s Universities, 2021.

9See: Universities Canada, 2018.

10See: Teaching and Learning Support Services, 2019.

11See: Ontario’s Universities, 2021.

12See Figure 3, taken from Adams & Zúñiga, 2016, p. 112.

13See: Adams and Bell, 2016.

14See: Adams & Bell, 2016; Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017.

15See: Burgstahler, 2015; Adams & Bell, 2016; Styres, 2017; Eyler, 2018; Tobin & Behling, 2018; Tomlins-Jahnke et al., 2019; Fritzgerald, 2020.

16For example, women, Muslims, Black persons, disabled persons, trans persons, and young people in general.

17See: Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017; Tuhiwai Smith et al., 2019.

18This series of questions is based on the work of Fox (2018, p. 122–125).

19See: Adams & Bell, 2016; Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017; Styres, 2017; Fox, 2018; Swiftwolfe, 2019.